remnant, 2013

archival Inkjet print

16 ½ x 21 inches

edition of 3

feathers and friction 1 – 18, 2013

blackout cloth, vintage clothing, paint, rope, silk bondage rope, feathers and leather

varying dimensions

songbird, 2013

fabric, vintage clothing, paint, rope, silk bondage rope, feathers and leather

29 x 13 x 10 inches

bucolic,2013

blackout cloth, vintage clothing, glass taxidermy bird eyes, thread and paint

27 ½ x 29 inches

erasure, 2013

archival inkjet print

15 x 20 inches

blackbird (shelf 1), 2013

fabric, vintage clothing, wood, vintage glitter glass, paint and feathers

12 x 12 x 8 inches

patterns of flight, 2013

archival inkjet prints and specimen pins

dimensions variable

edition of 3

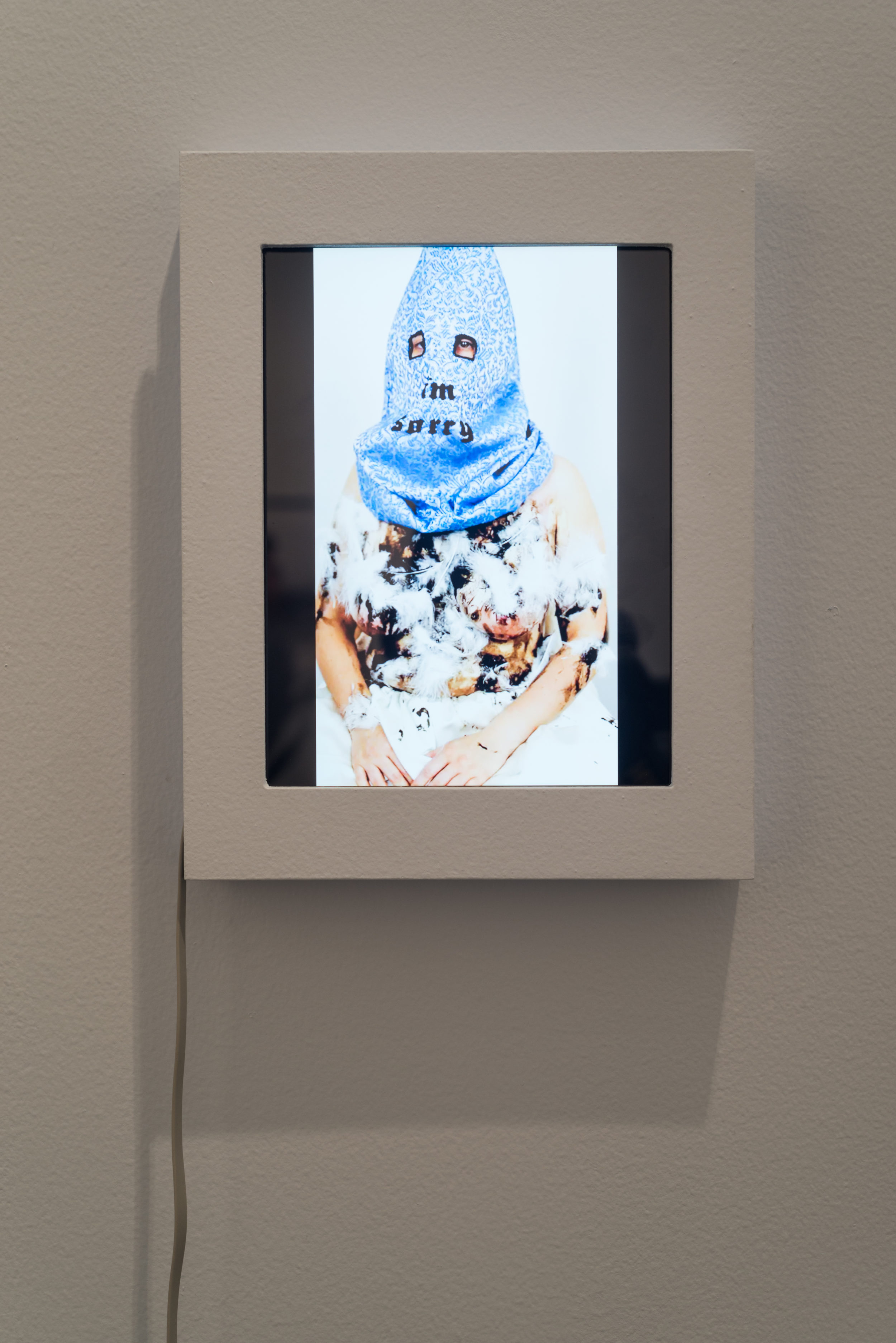

bluebird, 2013

video, 1:18 looped

October 4- 26, 2013 at David Shelton Gallery, Houston, TX

Margaret Meehan: even before, after, we were them

One of the few memories that Irving Berlin has of his childhood in late 19th century Russia is an image of himself as a baby, swaddled in a warm feather quilt, and lying by the side of the road as he watched his home burn down to the ground. His house, like those of so many other Jews at the time, was attacked by Cossacks. Later, after emigrating to America, Berlin wrote “Blue Skies,” a song about bluebirds, hope, and happiness. Its cheerful tone speaks to the ways that immigrants often adapt to a new country, embracing the optimism of a new nation’s promise. Forty years later, Paul McCartney was in Scotland reading about the US civil rights struggle and he wrote “Blackbird,” a song about a winged creature; he sings, “you were only waiting for this moment to arise.” The birds in these songs use flight for freedom, a potentially saccharine and predictable metaphor. But if we look deeper into the social and political contexts from which the songs emerged, we can see something more layered and nuanced.

Both songs are a part of Margaret Meehan’s exhibition at David Shelton Gallery, and they speak to the major components of her most recent body of work. There are some simple things like the colors black and blue and the complex symbology of a bird in flight. But Meehan’s work also pictures the violent mechanisms of hegemonic power and the gathering of resistance against them. It is not a story about one particular minoritarian struggle like pogroms against Jews or the Jim Crow South. It is not about race, ethnicity, class, gender, or sexuality per se. Rather, Meehan’s work is about the forms of otherness that occur in many different situations.

Like much of Meehan’s past work, this project began from researching a set of American histories, which span the past 150 years – a time of radical social upheaval with a deep and ongoing legacy in the present. One foundational book that was key to her thinking is Southern Horrors: Women and The Politics of Rape and Lynching by Crystal N. Feimster. The book chronicles the situations in which women were lynched, murdered, tarred and feathered, whipped, or raped in the American South between 1880 and 1930. According to Feimster, this was because race and sexuality were intertwined in a society predicated on the power of white male patriarchy.

One detail from this history that Meehan has focused on is the practice of tarring and feathering, which, like lynching and rape, is a way to objectify a body, to take away its subjectivity and humanity. These are practices that seek to transform an individual subject into an anonymous piece of meat. To tar and feather is to transform a person into an animal, specifically a bird, but not the hopeful symbol that Berlin and McCartney invoked, which used a bird’s plumage as the basis of a celebratory ritual. Instead, this practice evokes other meanings that birds can represent, like the threatening dread of a magpie, raven, or crow.

Meehan is interested in the ways in which anonymity, the erasure of subjectivity, is used and performed in sometimes contradictory ways. It can become a method of punishment or empowerment for a variety of ideological positions. For instance, the practice of covering one’s face with a hood or mask is something that can range from the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to prisoners at Guantanamo or Abu Ghraib to Pussy Riot to cofradías hoods, worn by an order of Spanish Christians to symbolize Catholic humility.

The KKK used hoods to hide their identity. This seeming anonymity allowed them to enact violent racist behavior. The Russian feminist activist punk band Pussy Riot also used masks—in their case brightly colored balaclavas—to hide their identity while protesting the repressive conditions of the Vladimir Putin’s policies and the Orthodox Church. The US military uses hoods to make prisoners feel a sense of disorientation and dislocation, cutting off sight and restricting hearing and breathing. It is a practice that the United Nations has concluded constitutes torture.

The hood is just one means of shaming an individual. Public humiliation has also been embedded in educational institutions through the practice of the dunce cap, which bad children had to wear while facing a room’s corner. Other forms of institutionalized shame included the yellow star used by the Nazis, which has its historical roots in the yellow patches of cloth that Jews were forced to wear in a number of Medieval European cities. This practice grew out of the Roman policy of marking prostitutes with a yellow badge. These are forms of shaming by adding a marker, a covering or an adornment of sorts. But humiliation can also be practiced by taking things away, like shaving victims’ heads or forcing them to undress.

The key to understanding the difference between the use of a hood by Pussy Riot and the US military in Abu Ghraib is the question of agency. When one chooses to hide one’s identity, or when one feels shame and covers one’s face as in the act of mourning, a subject retains a sense of freedom to think or to feel. Hiding or covering one’s self makes explicit the boundaries of a person’s private being. But when one is publicly humiliated, through mechanisms like a hood, a dunce cap, tarring and feathering or simple nakedness, not only is the identity of an individual erased but also their freedom. The boundaries of their private selves are penetrated, laying a person bare.

The sculptures that make up this exhibition, along with the repeated found photograph of an anonymous woman, are grounded in the 1950s, a moment in American and Western European history where the question of freedom was emerging in a new, post-war reality. Civil Rights, Feminism, Situationism, McCarthy, the Algerian War, and other struggles were bringing forward questions of race, gender, class, and colonialism in ways that would explode more fully in the 1960s. Meehan has taken scraps of vintage 1950s black clothing, like fragments of a moment of latent revolution, to make up these sculptures in ways that combine the ambiguity of their use for shame or defiance.

Some of the sculptures and photographs in this exhibition seem similar; they are made from the same materials and organized in groups. This use of the multiple, a longstanding trope in Meehan’s work, can be just as ambiguous as the hood. A group of similarly dressed people can seem like a mob or an army that erases individuality within its hoard and also lashes out against difference from its own characteristics. This phenomenon oddly reveals a formal similarity between Joseph McCarthy’s attacks on communists and homosexuals and Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which sought to root out capitalist elements from Chinese society. But a group of individuals gathering together in a public space can also signal protest against injustice, as in the case of the 1917 protest march against lynching held in New York or the annual international “Take Back the Night” rallies against rape and other forms of sexual violence. A group can assemble collective power to either attack or defend the rights of the individual.

Finally, Meehan uses the presence of nature—including an image of the sea and the recurring repetition of branches as well as birds—to evoke the Romantic paradox of the sublime. Nature, in this sense, can edge away from the forces of political or social violence. It is the blue sky that Irving Berlin’s birds fly to. It is the imagined forest at the city’s edge or the horizon across the sea that lies beyond the troubled times of today’s social ills.

But nature’s beauty is also reflected, inhabited and emulated through rituals that we have incorporated into our own popular culture. We have inscribed the transcendent power of nature’s patterns into our own lives. When a woman like Joan Crawford wears a set of black feathers, staring with sly defiance into the camera, she is evoking the power of the natural, embracing her feral nature. When Alexander McQueen encases a model entirely in black duck feathers, he takes this heraldry to the next step. While there is a formal echo of tarring and feathering in these images, once again, like the use of the hood, the fundamental issue is agency.

Margaret Meehan’s exhibition is predicated on history. It is a set of images and stories and patterns of behavior in multiple societies at multiple times. There is both savagery and beauty in these stories, but the main thing that she wants us to remember is that, while we might have progressed in some regards, we must never forget that we were them: at some point in our own histories, or in our current reality, we were the member of a majority that looked suspiciously at difference. But we were and are looking toward a horizon, climbing the trees, and trying to fly. We search for a way to see the bigger picture and a way out of the troubled times in which we live today.

-Noah Simblist is an artist, writer, curator and Associate Professor of Art at SMU in Dallas, Texas.

*Essay written for broadside collaboration with Margaret Meehan and Travis LaMothe.